Andrea Bianconi

Curated by Giuseppe Frangi

Casa Circondariale “Francesco Di Cataldo”

San Vittore, Milan

3rd April and 9th May 2019

ANDREA BIANCONI AT SAN VITTORE

Giuseppe Frangi

The artist is present: this is the distinctive mark of the artistic form of performance. The artist comes into play with his body in order to rediscover an intensity of relationship with the world around him, which the work itself seems no longer able to guarantee. In short, performance is that simple and extreme form through which the artist says to the world: “I am here”. The sense of this “being present” is that it is always a destabilising element, because it introduces other logics and other points of view. With the performance, the artist puts himself in play, without mediation; above all, he is called upon to prove a radical sincerity, which shakes and creates short circuits.

Sincerity is one of Andrea Bianconi’s defining qualities; an artist who always plays it close to the vest, even when working with traditional media, but who finds his most congenial field of expression in performance. Born in Vicenza in 1974, Bianconi has performed in every corner of the world, from Moscow to Shanghai, Venice to New York. Each time he makes incursions like a true corsair, following unpredictable scripts that amuse, sometimes move, but always take you by surprise. In his performances, Bianconi transforms himself into a fairy-tale character, a pure and wild hero who enchants us with his strange rituals and bizarre catchphrases.

Andrea had long dreamed of being able to do a performance in a sensitive place like a prison. I believe that the reason for this lies in a very simple fact: for Bianconi, performance is first and foremost an experience of freedom, because it is a space for action that does not obey a logic, let alone a rule. A space in which the artist is not called upon to deal with a “why”. Freedom is guaranteed by the fact that the performance is once and for all; once it has happened it dematerialises and lives only in the documentation of what has happened. This means that there is no object to sell and therefore the performance is also free from the rules imposed by the market. Bringing an experience of such profound freedom to a place like the Panopticon from which the rays of San Vittore radiate is, as you can easily imagine, a significant event. It is a first-hand verification of freedom as an irreducible factor of human nature. Bianconi then adds other elements that reinforce this dimension.

The performance takes place around the cages: they are an oppressive symbol. The cage is clearly an emblem of a condition of confinement and a symptom of existential fragility. On the one hand, the cage separates us from the world, but on the other it also protects us from the world. Bianconi’s intervention produces a short circuit and calls into question these instinctive certainties. His cages, which fly around hanging in space, with their doors regularly open, are not only emptied of all their negativity, but are called upon to participate in an unexpected and bizarre ritual, which transforms them into cheerful creatures out of place and out of function. So much so that at the centre of the Panopticon, on the podium where the priest sits for Mass on Sundays, Bianconi has placed a sculpture that is nothing more than a cage that has been eviscerated and “opened” as if it had been transformed into the corolla of a flower. The cage, under the action of the magician Bianconi, changes its nature in every sense. The performance, with its verbal catchphrases, becomes a celebration, a rite of thanks for this transfiguration.

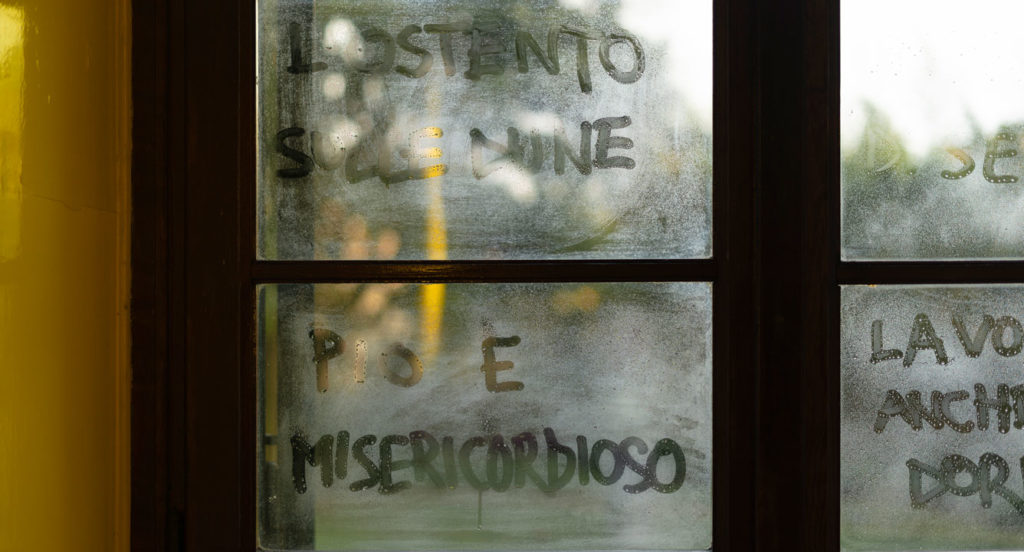

The other characteristic of Bianconi’s presence in San Vittore is perfectly connected to what we have described so far. The arrow is a tautological sign: there is no need to assign it a meaning. The meaning of the arrow is contained in the simple strokes that make it up and which express a going, a moving, a leaving. The arrow is the antithesis of the status quo. It is an instinct that looks beyond. It is the frank expression of an expectation. It is a desire for change. It is an attempt to give oneself a direction. Bianconi’s arrows, which mark Marco Casentini’s coloured walls in the entrance corridor, carry all these possible messages.Andrea Bianconi’s presence in San Vittore is the result of a project developed with Casa Testori. I think it is important to underline this because in this way a sensitivity that had distinguished Giovanni Testori, as a person and as an intellectual, is renewed. Testori had come to San Vittore several times and had solicited a different kind of attention from the city. Being here, bringing an artistic gesture that speaks of freedom and desire for change, is a way to renew his conviction that culture must always mix with life in order to be true.

THE PERFORMANCE

Come costruire una direzione (How to build a direction), elaborated by Andrea Bianconi with the production of Casa Testori, is a performance staged during the 2019 Milan ArtWeek in the San Vittore prison, inside the famous Panopticon from which the six rays of the Milan prison structure depart.

Andrea Bianconi has set up 24 cages – one of the symbols of the artist’s poetics – which have been positioned in front of the gates of the six rays. The cages, of course, are a mirror reflection of the prison condition, but Bianconi’s action wanted to overturn the sign and give them a liberating connotation: they were the cages of our desires, whose doors are therefore always open.

On the central podium of the Panopticon, where Holy Mass is celebrated on Sundays, Bianconi had placed a large sculpture made for the occasion: a cage whose walls were opened almost to form a flower and, symbolically, wings, another symbol of Bianconi’s art. The performance was attended by the CETEC Dentro/Fuori San Vittore company, which includes some of the female inmates. With them, Bianconi sang a pressing, obsessive and utopian tune, repeating the words “Fantastic Planet” hundreds of times, following a script set by the artist. “Fantastic Planet“, because, as the artist explains, it is the product of everyone’s imagination. And imagination is an intrinsically free factor, not one that can be “imprisoned”.

The performance in San Vittore was a deeply felt performance by the artist because – unlike what had happened previously – he was not alone. At his side were 10 female inmates, special actresses who sang and repeated with him, almost obsessively, the claim “Fantastic Planet“, because everyone can always imagine their own fantastic world.

If the cage is the place of a desire to be freed, the arrow becomes the symbol of this desire taking flight. Therefore the performance ended with the singing of a nursery rhyme written by Bianconi to the tune of a popular children’s song entitled La Freccia (The Arrow). The nursery rhyme was first sung by the artist alone, then repeated with the prisoners.

“I am enthusiastic about this experience, San Vittore is a special, delicate place and my performance is intended to convey the message that for everyone there is a possibility, a perspective, an opening through which to free their desires”, said Andrea Bianconi.

“Art brought inside the walls of a prison can be an experience of great value, if, through the beauty and unpredictability of its proposals, it succeeds in stimulating positive paths of awareness and change”. These are the words of Giacinto Siciliano, director of the San Vittore prison, which encapsulate the profound meaning of the performance to which, not by chance, Andrea Bianconi has given the almost programmatic title of Come costruire una direzione.

The project also included an exhibition of 50 drawings displayed for a month in the long corridor leading to the Panopticon rotunda, with the arrow as the dominant motif.

The arrow, in Bianconi’s grammar, is a sort of happy obsession, giving form to the irrepressible need to desire. The arrow is liberating energy, but it is also direction: it therefore indicates a possible path, which is unique and unrepeatable for each person, a positive sign carried within an environment marked by its nature by opposing dynamics. But as Bianconi explains, “art is always open to the future, even when it conveys dramatic messages. As far as I am concerned, the title of the exhibition gives a clear indication, which I instinctively feel is mine: I tend to look at the good and not the bad. For me, art is a matter of courage that stimulates other courage in people”.