Room 6

“The world is changing. It is superfluous to document such a serious and extensive fact: culture, customs, systems, economics, technology, efficiency, needs, politics, mentality, civilisation… Everything is on the move, everything is changing. This is why the Church is in difficulty”.

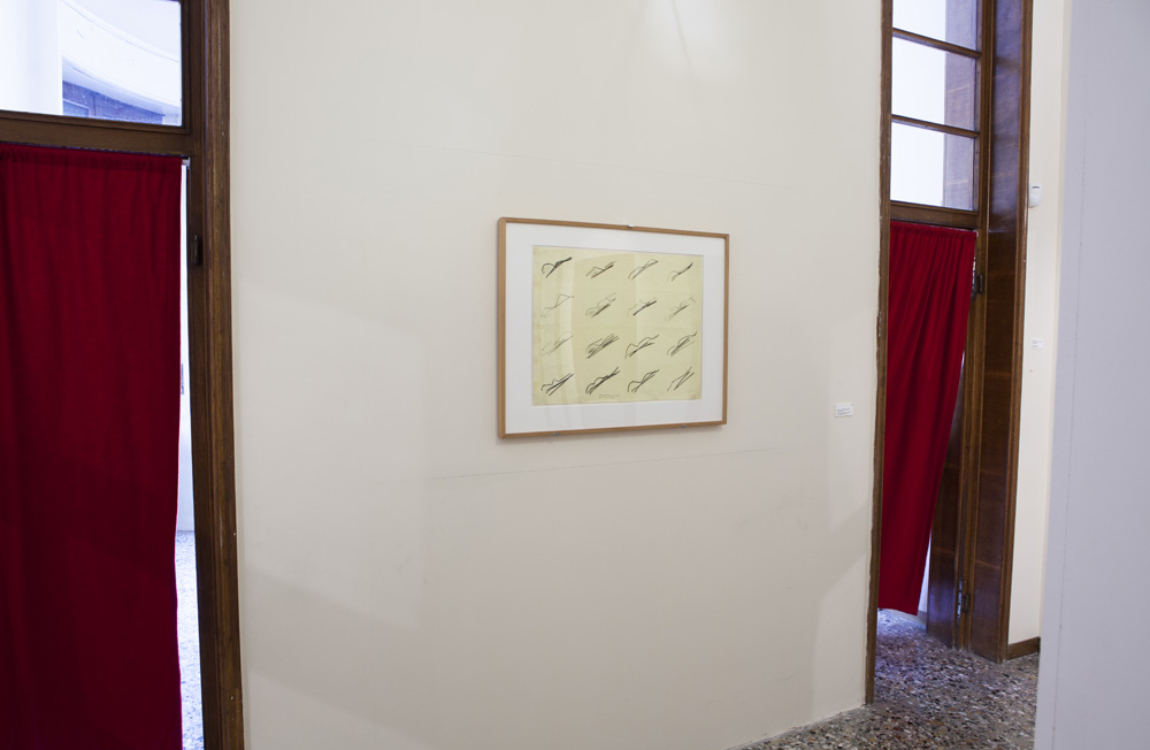

This is the beginning of a dramatic speech that Paolo VI delivered on 11 September 1974 during a Wednesday audience at Castelgandolfo. “What remains of our religion? What remains of the Church?”, the Pope asked himself, noting the advance of a modernity that was digging an abyss behind it. Only Pasolini grasped the novelty of that speech: “a lightning-fast look at the Church from the outside”, he defined it. On 22 September, the writer published an article in the Corriere newspaper entitled I dilemmi di un Papa oggi (The dilemmas of a Pope today) and in the panel we present the copy of the original, which arrived by teletype from Rome to the Milan editorial office in Via Solferino. It is the speech republished in Scritti Corsari with the title Lo storico discorsetto di Castelgandolfo.

Pasolini had never hidden his sympathy for Paolo VI: “He suffers what I suffer”, he confided to the English journalist Peter Dragadze. “What makes Paolo VI likeable is his tormented intelligence: and the fact that he has no external qualities of pleasantness and, indeed, of sympathy, is almost tender”.

As for Paolo VI, his reaction to the news of Pasolini’s death is very significant. This is the testimony given by Monsignor John Magee, one of the Pope’s secretaries, to the journalist Andrea Tornielli: “I remember the day when Pasolini’s death was announced on television. Monsignor Macchi exclaimed: ‘Ah! You see the Lord has a way…’. Paolo VI remained motionless. Macchi explained what this man had done, in his opinion, to the detriment of so many young people. The Pope stood up, there was still an image of Pasolini on the screen: ‘Requiem aeternam dona ei Domine’ – he said, making a sign of the cross: ‘Now let us pray together for this unhappy soul’. That was his reaction”.